WHATEVER WENT WRONG WITH WINNIE?

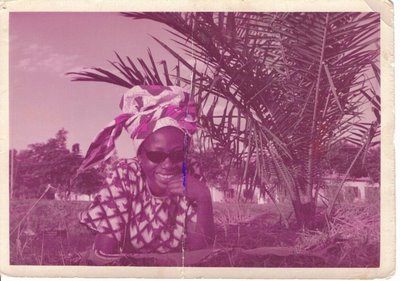

He stood by his wife, still captivated, when those around him denounced her for violence and treachery. Now, even Nelson Mandela himself has come to see the truth: that he has loved not wisely but too well. John Carlin reports John Carlin Wednesday 29 March 1995 In December 1989, Nelson Mandela sent Winnie his last Christmas card from prison. "Darling, I love you," he wrote in big letters. Some months earlier he had sent her a birthday card with the message, "What a difference it makes in my life to have you". I interviewed Winnie Mandela at the end of January 1990, two weeks before her husband's release, and saw the cards on display on the mantlepiece of her home in Soweto, the place where Stompie Moeketsi had been murdered a little over a year earlier. I knew full well at the time that this was where Winnie's bodyguards, the so-called "football club", had beaten the 14-year-old boy to death. Yet, as I recall now with shame, I forgot all about Stompie the moment she entered the room. Winnie is a mountain of a woman, tall, more solid than fat, with formidable shoulders. She is old enough to be my mother. But during the 40 minutes I spent alone with her I was absolutely, helplessly beguiled. She had kept me waiting for two hours in the lounge while she performed her morning toilette. When she appeared, she glowed. She was regal and coquettish at the same time. Eyes big and bright and staring straight into mine, she purred suggestively about her impending reunion with her husband. She felt like a young bride all over again, she said. Nelson, they say, was struck like a thunderbolt the first time he saw her. He was in his late thirties, she was 20. He was married to Eveline, a sweet, soft, gentle woman who has spent the second half of her life running a grocery store in the remote little Transkei village of Comfimvaba, never remarrying. Nelson and Eveline had three children. They had been married for more than ten years the day he met Winnie. Eveline had no chance. Within months, Nelson divorced her and married Winnie. As time has shown, she was his blind spot, his fatal flaw. My eyes were opened nine months later, at the conclusion of an investigation with the BBC Radio's File on Four into the affairs of Winnie's football club. During that investigation we learnt some of the truth about Winnie. We learnt that Winnie had founded the club in 1986, ostensibly to provide amusement for unemployed young men, really to create around herself a queenly retinue that evolved over the next three years into a thuggish neighbourhood mafia. We met Dudu Chili, a neighbour of Winnie's, whose home was set on fire by the football club and whose 11-year-old niece, Finky, they shot through the head. We also met Nico Sono, who told us he had last seen his son, Lolo, battered and bleeding in the back of Winnie's van. Winnie was sitting in the passenger seat. Mr Sono pleaded with Winnie to let him go. She said: "No, he's a sell-out." That was in November 1989, more than a month before Stompie died. Mr Sono has never seen his son since. From trawling through court records, we established that members of the football club had carried out an additional 12 murders, one of them with Winnie's direct authority. We also learnt that senior members of the United Democratic Front, the African National Congress by another name before the organisation was unbanned, had a good idea of what exactly had been going on. In March 1989, they had issued a statement, led by the ANC's present secretary general, Cyril Ramaphosa, denouncing the football club's "reign of terror" in Soweto and charging that if it had not been for Mrs Mandela, Stompie would still have been alive. For a long time Winnie was Nelson Mandela's blind spot. When he could see the future of the country so clearly, he failed to see her nature. Mr Mandela himself refused to believe a word of it. Through Winnie's trial he stood by her, besotted, unpersuaded of her dark nature by the judge's verdict in May 1991 that she was guilty of kidnapping and assaulting Stompie and three others. He also refused for a long time to see that two years after his release she was carrying on an affair with Dali Mpofu, a lawyer half her age. It wasn't as if she had gone out of her way to hide what was going on. She appointed him her deputy in the ANC's social welfare department; she travelled with him to the United States, flying by Concorde from London, staying at the Beverly Hills Hotel. Early in 1992, she found out Mpofu was having an affair with another woman. It all spilled out into the open. On 17 March she wrote him a letter, later published by the Johannesburg Sunday Times. "You're running around fucking at the slightest emotional excuse," she wrote. "The fact that I haven't been speaking to Tata [Nelson Mandela] for five months now over you is no longer your concern. I keep telling you the situation is deteriorating at home. You are not bothered because you are satisfying yourself every night with a woman. I won't be your bloody fool, Dali." A month later, in April 1992, the ANC fired her from the welfare post and Mr Mandela announced that the marriage was over. Her world seemed in ruins, as it does now that President Mandela has fired her from her job as deputy minister of culture. But she bounced back. She burned with political ambition. She would not be denied the glory she believed was her due after waiting 27 years for her husband to leave jail. So she played Evita. She did what few other senior ANC leaders did: she would turn up in her Mercedes Benz to visit the poorest of the poor in the squalid squatter camps of Johannesburg and the Cape, she incited the youth with rabble-rousing speeches. Even though her fortunes fell once more in July 1993, when the ANC Women's League suspended her for displaying "defiance, insubordination and total disloyalty", she went out of her way to prove her accusers right by writing an article published in the South African press accusing the ANC leadership of rushing "with unseemly haste" to cut a deal with FW de Klerk's National Party, "to wrap themselves in the silken sheets of power". She was clever. With her populist message she tapped into a radical vein in the ANC - a small constituency but one potent enough to make it impossible for the leadership to ignore her. When President Mandela appointed his government, he made her deputy minister, guided by the same principle which had secured South Africa's successful transition to democracy: inclusivity. The coalition government, as he explained in an interview a month after his inauguration, was "full of people whose hands were dripping with blood." Why make an exception of Winnie? The logic was that once inside the government, she would toe the line. Mr Mandela made his judgement with his head, not with his heart. Despite recurrent reports in the media that the couple would reunite, the evidence suggests that now he cannot stand the sight of her. For his 75th birthday party in June 1993, he invited 650 guests. Winnie was not among them. At their daughter's wedding later that year, he turned his back on her when she approached him for a dance. Few people know what his real feelings towards her are. As a politician he is warm and generous. In his personal life, he is a sphinx. But one friend in whom occasionally he confides let slip last year that Mr Mandela had told him he could never forgive his wife. "Why not, Nelson, when you've forgiven the people who kept you in jail all those years?" the friend asked. Mr Mandela could not reply. It was again with his head and not his heart that he made the decision this week to dismiss her from his government. On the one hand, she had hardly behaved with the propriety expected of her office: during her first month in government she spent on bodyguards 40 per cent of the amount spent by the other 39 ministers and deputy ministers combined; she accepted a gift of a luxury home in Cape Town from a benefactress who, it turned out, had a diamond-smuggling conviction; she was sued in court for non- payment of a Lear-jet she hired to fly to Angola, allegedly to pick up diamonds. On the other hand, she openly criticised the government - resorting to her old populist ways - and she consistently disobeyed presidential orders. Mr Mandela calculated that the benefits of keeping her in government were now outweighed by the negative impact her scandals were having on South Africa and the world at large. He knows that she will not give up without a fight, that she may attempt to stir unrest among sectors of the black community frustrated at the government's failure to do the impossible and provide housing and jobs for all. For the long years while he was in prison she was his emotional support; he seemed her point in life. Now they are enemies and Mr Mandela's hope is that his authority will nullify her worst efforts to rekindle her ambitions. There are those who still believe that she is sincerely driven by a desire to do good not for herself, but for her people, who see her as a victim of circumstances, to be understood and therefore forgiven. They point to the burden bequeathed by her husband when he went to prison, to pursue "the struggle" while bringing up a young family alone, to her year in solitary confinement;they point to her constant harassment by the police, to her seven years of forced internal exile in the dusty little town of Brandfort, to her heroism in carrying the torch of the liberation movement during the Eighties, when all the other ANC leaders were in jail. I have had many arguments with such people. My answer is always contained in two words: "Albertina Sisulu", the wife of Walter Sisulu, who spent almost as long as Mr Mandela in prison, the mother whose sons and daughters were jailed and exiled, the politician who fought as bravely as Winnie, against odds as tough, but who remains to this day a model of kindness and moral rectitude. Mrs Sisulu and many other unsung South African heroines have suffered torments as bad as, if not far worse than, those of Mrs Mandela. Walter Sisulu is both a fortunate and a happy man. The tragedy of it all is that Mr Mandela, in the glorious winter of his years, is neither. Eyes set unflinchingly on a higher purpose, he has subdued his pain. One day, if he survives into retirement, he will look back, regret the sacrifice he has endured and ponder the thought that his life's greatest mistake was to have loved not wisely, but too well.